Discover our user stories and learn about the challenges they overcame with graph technology. In this post, our partners from tech4pets explain how their organization is helping animal welfare associations and authorities dismantle pet trafficking networks through the collection and analysis of online data.

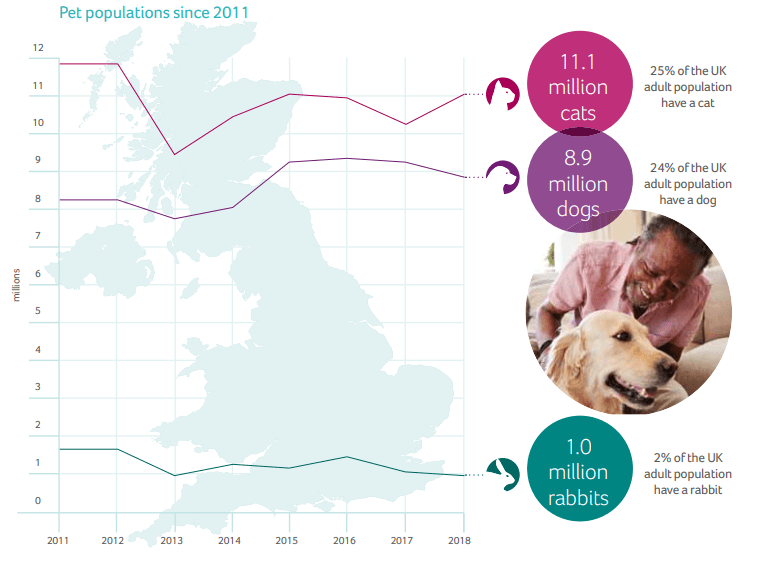

The pet market in the UK is huge and continues to grow. According to the 2018 PAW report by the pdsa, 49% of UK adults own a pet, with the following species breakdown:

- 25% of the UK adult population have a cat, an estimated total of 11.1 million pet cats

- 24% of the UK adult population have a dog, an estimated total of 8.9 million pet dogs

- 2% of the UK adult population have a rabbit, an estimated total of 1 million pet rabbits

The pdsa estimate that the minimum lifetime costs of owning these pets can range from £6,500 to £17,000, depending upon species and breed. This does not include the costs of purchasing the pet(s) initially and costs for any ongoing veterinary attention. For “fashionable” breeds, the costs of purchasing your pet can often be very high (£1,000 and upwards), as can the veterinary costs which arise with some of these breeds, particularly “flat-faced” dogs, cats and rabbits.

Given the sheer number of animals owned, as well as the ownership costs, it is clear that the size of the pet industry is significant. The same pdsa report also studies how owners research before purchasing a new pet, as well as where they ultimately find their new companion(s).

Unsurprisingly, the internet features prominently in the results, both for pre-purchase research and as the place where both animals for sale (breeders/private sellers) and for rescue (charity rescue shelters or rehoming centres) are found. The level of research performed and due diligence exercised by potential owners varies widely from case to case.

Perhaps inevitably, this combination of high cost, ready demand, unprepared buyers and the internet attracts unscrupulous sellers. These “problem” sellers can take many forms, e.g.:

- Unregistered “backyard” breeders, running what is effectively a commercial operation whilst masquerading as a private “hobby” breeder.

- Large scale “puppy mills”, churning out “fashionable” breeds at high volumes with very low welfare standards and often re-sold through third parties.

- Puppy smuggling operations, taking advantage of free travel areas (Ireland -> Great Britain) or abusing “Pet Passport” schemes to breed pets at low cost in one country and then resell them in higher spending countries (EU-wide).

Some of these operations have also been linked to other forms of public offence such as tax avoidance, benefit fraud, smuggling, organised crime and money laundering.

Organisations, both governmental and non-governmental, have known of these issues for some time and have active projects to both educate the public and crack down on the most prolific offenders. The work of the Pet Advertising Advisory Group (PAAG) is of particular note. They work closely with online classified sites and industry associations to improve the level of information offered to sellers and control the types of selling activity performed.

To truly tackle any problem though, you first need to accurately understand the size of the issue, which is where the work of tech4pets comes in. In the past, understanding the market has been performed manually using volunteers or through surveys. As the sale of pets increasingly goes online, monitoring both the size of the market and identifying problems therein becomes a scale problem which can really only be tackled using technology itself.

The technical challenges with tracking the trade in pets are multi-disciplinary, ranging from data acquisition all the way through to bulk analysis and visualisation. Broadly speaking though, the key challenges are:

1- Scraping of classifieds site pet adverts in a flexible, resilient yet disciplined way. Every piece of content acquired could, potentially, form a piece of evidence in a future prosecution and must be treated as such. We try to work alongside the classifieds sites themselves to ensure we operate in an unobtrusive way, but do so at a rate and scale which allows the maximum market coverage.

2- Availability and timeliness. For market monitoring to be successful, near 100% uptime must be the aim. Extended outage periods potentially mean lost records and an incomplete intelligence picture.

3- Employment of open source intelligence (OSINT) techniques to improve the depth and breadth of understanding about the content we hold. This can range from utilising natural language parsing right through to cross referencing against other open source datasets.

4 – Our stakeholders require a varied set of views over the data we produce. This can range from regular high level market reporting, right through to selling pattern analysis and the ability to interrogate specific records interactively.

5 –“Problem” sellers, in varying degrees, go to some lengths to hide their identifies and obfuscate their activity. Selling networks that comprise hundreds of user IDs and dozens of mobile phone numbers are not uncommon. In the cases of puppy mill and smuggling rings, these networks often cover multiple legal jurisdictions.

6 – Duplication of adverts represents a significant challenge. Many sellers, to get maximum exposure, use more than one classified advertising site concurrently and repost their adverts many times a day, sometimes for weeks on end. This creates problems when trying to actively distinguish between a seller with many animals to sell versus a seller with a single animal or litter who is maximising their efforts to sell or rehome an animal.

7 – There is no “one pattern” of activity per site, advert, seller or indeed species. Every situation is truly unique.

Graph technologies have many features which lend themselves to solving a lot of the problems inherent in a project of this type.

Crucially, storing data in a graph database allows the kind of flexibility we need to cope with such a wildly varying dataset, especially when compared to a traditional RDBMS implementation. Of particular note is the ability to store attributes on edges as well as vertices, allowing some creativity when performing deduplication and network identification.

The technologies chosen offer us the ability to do large scale analysis against the entire graph or subsets thereof. A typical approach is to perform community detection (all subgraphs) to identify distinct seller networks, then to perform clique detection on specific seller networks to understand how many animals might actually have been offered for sale.

The output from this process varies from the very traditional (excel spreadsheets or PDF reports) right through to interactive visualisation using tools like Linkurious Enterprise, depending upon the stakeholder needs or audience. Graph visualisation is inherently intuitive and allows interrogation of fairly complex datasets by non-specialists with basic training.

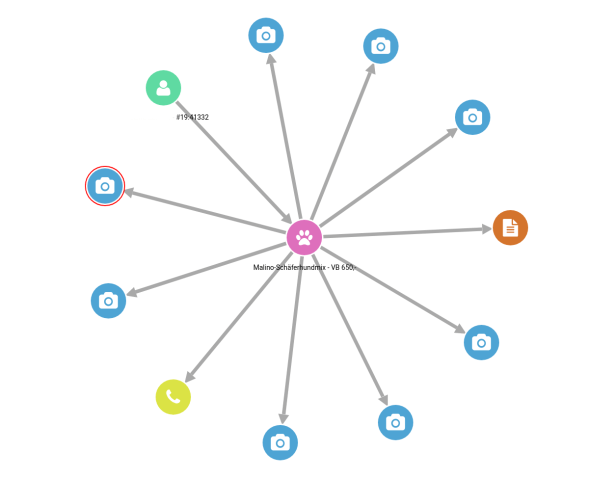

The majority of advertiser profiles are simplistic and fit the pattern of someone rehoming their own pet or, perhaps, selling the offspring of an accidental or one-off litter. The graph for that type of activity generally looks something like this:

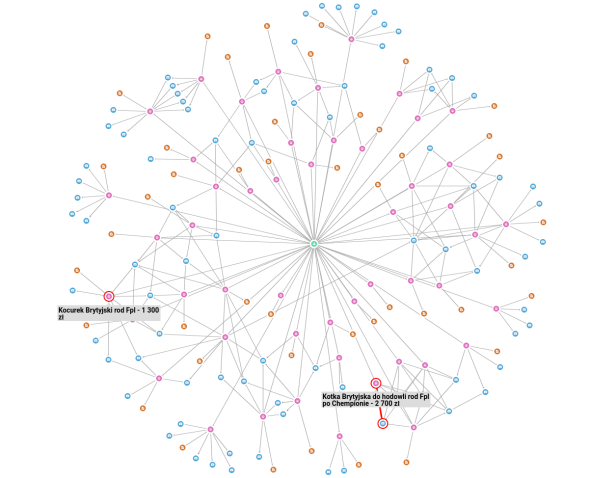

In contrast, other advertisers exhibit activity patterns much more akin to an organised network, often covering several species, many advertiser profiles and sites. Such activity, when plotted, is dramatically different from the “normal”:

The real power of the graph, and accompanying tools such as Linkurious, is the ability to efficiently store, manage and analyse data covering such wildly varying situations.

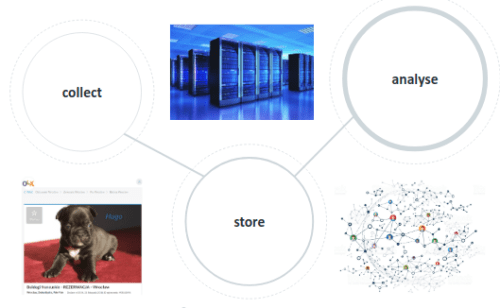

The solution architecture is deliberately divided to support two distinct phases of activity: collection and analysis. Implementing the project in this loosely coupled way allows to cater for the differing requirements of the two activities.

The collection phase provides for scalable, resilient and flexible collection of pet adverts from monitored sites. New adverts are identified, retrieved and stored along with relevant artefacts such as any accompanying photos. As part of this process, parsing is performed to extract relevant data and metadata. This data is cleaned up, augmented with supplementary datasets and processes, then stored ready for the analysis phase. Collection runs 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

The analysis phase regularly extracts new data from the collection database and stores it in a graph database. In early phases of the project the graph database used was OrientDB. With the growth of the project and the need to support data storage in multiple regions, we now use JanusGraph backed by Apache Cassandra as our graph database of choice.

At this point, the graph can be interrogated by batch and interactive processes, according to the needs of stakeholders. This can vary from scheduled whole-graph analysis using Gremlin to interrogation of specific subgraphs using bespoke visualisations and tools like Linkurious Enterprise. Stakeholders often have intelligence leads of their own (a phone number, for example) and use the tools to interrogate the database on an ad-hoc basis to view the breadth and type of advertising activities associated with those leads.

Whilst the use of graph technologies is a great boost to projects like this, there have been some lessons learned as the project has grown.

One of the key decisions was the separation of collection and analysis. All data collected from online sources is inherently “dirty”. From the great variance of content quality through to simple typos and misclassification, it has proved critical to keep “dirty” data out of the graph. Not only does such data cause false matches, it is also more difficult to remove from the graph once widespread. The temptation to “graph early” is strong, but in this case has to be resisted.

Our typical analysis, as described above, tends to be two-phase: identifying networks or bulk sellers using community detection, then classifying their activity in more details through the use of clique detection. Whilst the graph, as persistently stored, strongly supports the former activity (community detection), it has proved inefficient to store all the data required to do the latter (clique detection) in the graph itself. As the majority of sellers are deemed “not-of-interest” for deeper analysis, storing everything we need to identify cliques for all is unnecessary and causes graph “bloat”. Instead, after identifying sellers or networks “of interest” we create dynamic (and temporary) subgraphs allowing deeper clique analysis to be performed in isolation. Not only does that prevent such graph bloat, but allows for more flexibility and innovation (and therefore accuracy) in the analysis of suspect activity. Flexible and powerful software such as networkx (Python) has proved invaluable in this approach.

Perhaps more obviously, it is critical to plan for growth at an architectural level. The tech4pets project started as a limited effort to monitor sellers of pet rabbits in the UK on behalf of the Rabbit Welfare Association (“Project Capone”). We now perform large scale analysis for several species in the UK and Ireland on behalf of prominent animal welfare charities, trade associations and government entities. As a rapidly growing community interest (not for profit) project, the ability to scale horizontally and at as low a cost as possible is critical to our success.

Applying graph technology to the data tech4pets captures has provided tangible results in the fight to improve companion animal welfare.

Quite apart from capturing the sheer size of the trade (over 1.8m UK adverts collected since inception less than 3 years ago), we have contributed to changes in legislation designed to tackle problem selling. These contributions have ranged from briefing ministers for debates in parliament through to presenting at the EU Commission in Brussels on the subject of cross-border trade.

On the enforcement side, quite apart from identifying and quantifying problem sellers for various agencies, we have provided supporting evidence for investigations into problem selling, trafficking and animal welfare violations. The results of these investigations have ranged from closure of unlicensed premises or license enforcement, through to arrest and prosecution. For example tech4pet’s work has led to two raids on illegal puppy farms in Ireland, with 86 dogs recovered from one site and 39 from another.

About tech4pets: tech4pets is a UK-based community interest company (not for profit) which enables professionals from across the business and technology spheres to engage with animal welfare organisations by using their expertise for the common good. Get in touch with tech4pets.

A spotlight on graph technology directly in your inbox.