Anti-money laundering, or AML, is the regulations and procedures in place to prevent criminals from concealing ill-gotten funds.

Why is anti-money laundering necessary? Money laundering is global and it’s pervasive, and the size of the problem is staggering. An estimated $800 billion to $2 trillion, or 2 to 5% of the global GDP, is laundered through the financial system each year.

It’s a global problem, and the threat from money laundering has only grown larger in recent years. The victims are individuals, families, government institutions, private businesses, non-profit organizations.

Once the damage is done, it’s hard to undo. Less than 5% of assets lost to financial crimes like money laundering are ever retrieved.

But the true cost of money laundering is difficult to quantify. Anti-money laundering solutions are more and more costly. And there is a high human cost to these crimes. Money laundering covers up human, drug, and animal trafficking, environmental crimes, corruption, and more.

This article explores the ins and outs of money laundering - what it is, what common money laundering schemes are, etc - and anti-money laundering: managing AML risk, customer due diligence and KYC, AML compliance, money laundering investigations, AML technology, and more.

Money laundering is a financial crime that involves concealing the source of criminal funds to give them the appearance of legitimacy so they can be used in the legal economy.

Say you’re part of a criminal enterprise: you get your money from drug trafficking or some other illegal business. Or maybe you’re a government official who took a nice chunk of money from a business in exchange for a contract to build a new bridge in your jurisdiction in a procurement fraud scheme. Now you have to cover your tracks since you want to use that money, but you also don’t want the authorities to connect you to any wrongdoing.

Preventing, detecting, and investigating money launderers is important because the money they are hiding is connected to crimes with serious consequences for the economy - and for humanity as a whole. It’s money that’s used for trafficking drugs and humans. It’s money stolen from states. And it’s money that may be used to fund additional criminal enterprises.

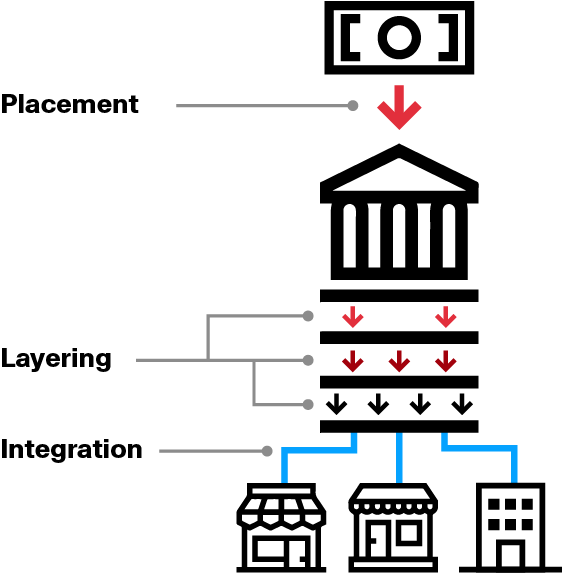

Money laundering typically (but not always) happens in three phases:

- Placement, during which funds are integrated into the financial system or into a legal business. If we’re talking about proceeds from crimes like drug trafficking, these assets will often be in cash.

- Layering is the process by which money is separated from its source, making it difficult for investigators to see exactly where the money went.

- Integration is when money enters the legal economy. At this point, the money appears clean and investigators can no longer see where it originally came from.

Since money laundering is by nature a secretive crime, it’s hard to come up with a precise estimate of exactly how much money we're talking about. Part of a money launderer’s job is to go undetected.

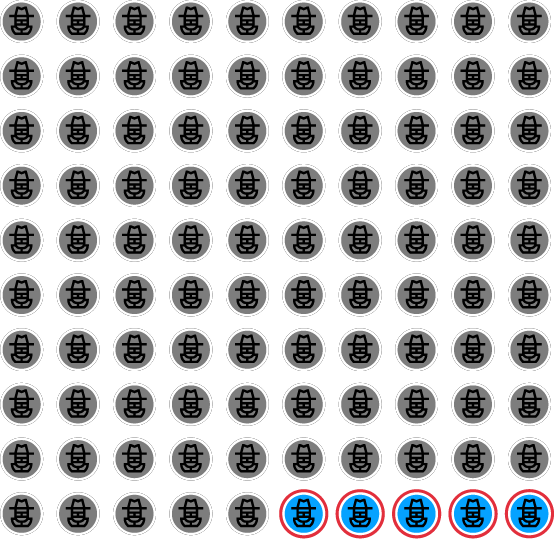

The best we have are estimates based on data available to us—and those estimates are jaw-dropping. Here are some key figures to put money laundering into perspective:

- An estimated 2 to 5% of the global GDP is laundered each year

- The illegal drug trade alone represents some $300 billion each year—a little more than the GDP of Sweden

- Only about 1% of criminal proceeds are ever seized

All that criminal money can have detrimental effects, undermining both the legal private sector, as well as the integrity of financial markets. And in most cases, once the money’s gone, you can kiss it goodbye forever.

Money laundering doesn’t always happen in these three phases, though. Many frauds and other crimes have gone cashless, just like they have in the legal economy. The proceeds from cashless crimes don’t need to be placed or integrated. All criminals need to do is to use layering techniques to distance themselves from the source of their dirty money.

Because money laundering is so complex, multilayered, and covert, preventing and fighting against it is no simple task. Here’s a quick look at some of the regulatory bodies and some of their landmark AML compliance decisions.

Established in 1989, the Financial Action Task Force published their landmark 40 recommendations to counter money laundering in 1990. They have since been updated to reflect changes in criminality trends and finance practices. The recommendations now account for increasing global use of cryptocurrency, for example.

The FATF doesn’t have enforcement power, but their recommendations remain the main standard for anti-money laundering controls and procedures.

With 35 member countries, the OECD works on fighting illicit financial flows. One of their landmark policies has been the establishment of the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) to create a global tax information exchange network. The purpose of the CRS is to combat tax evasion.

Increased collaboration is one of the keys to better anti-money laundering efficiency and more efficiency in the fight against financial crime more broadly.

US regulations have become a global anti-money laundering standard, since organizations doing business with the US must comply with them.

The most important AML legislation in the US is the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970. The BSA established compliance regulations for financial institutions operating within the US. The requirements include a risk-based AML program that includes customer due diligence, screening measures, and reporting and record-keeping standards.

The Patriot Act of 2001 expanded on the BSA, giving law enforcement additional investigative powers. The act also targeted financial crimes associated with terrorism, imposing more controls for cross-border transactions.

The US continues to build on their AML regulation. Most recently, the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) has imposed new changes, including to industries outside of financial services, such as real estate.

Just a year after the FATF published their recommendations, the European Union published its first anti-money laundering directive in 1991. The directive was then implemented as law, laying out regulations for compliance. Like the US, because of the size and influence of the EU, its directives act as a de facto international standard.

The EU has continued taking action through successive anti money laundering directives, the most recent one (n° 6) adopted in December 2020 and going into effect in June 2021. Some of the notable features within 6AMLD include consequences for aiding and abetting money laundering, a more extensive list of predicate crimes, provisions for greater cooperation among EU states, and harsher punishments.

Failing to do enough to counter money laundering carries heavy risks for financial institutions. Here’s what’s at stake.

- Huge fines. Financial institutions and other businesses still risk having to fork over millions or even billions in fines for breaching compliance regulations, or even for failing to put in place sufficient safeguards against money laundering and other financial crimes.

- Legal responsibility & imprisonment. In addition to fines, there can be other legal consequences for money laundering—or for failing to do enough to prevent it. A financial institution can lose its license to operate. Individuals involved in money laundering scandals within an organization may also face prison sentences.

- Loss of reputation. People and businesses may not want to work with a company that has been caught up in dirty business. Money laundering and other financial crime scandals can have a lasting impact on a business’s reputation and therefore on their bottom line.

Since money laundering is a complex problem, organizations need a multi-level approach that can adapt as money laundering threats evolve.

Financial institutions are required to establish a program for AML compliance with the legal frameworks in places where they operate. This involves determining a set of policies to ensure their business meets the legal requirements around AML. Those policies must conform to the regulations in place where the financial institution does business.

One of the most important ways of mitigating the risk of financial crime is to first of all know who you are working with. Introducing: Know Your Customer (KYC), also called Customer Due Diligence (CDD). KYC is a set of activities done during onboarding that help ensure an organization knows who their customers are and the money laundering risk they may pose. This also helps determine what normal behavior looks like for a new customer. Having a baseline of normalcy helps flag anomalies down the road.

Risk assessment helps financial institutions evaluate and document where the greatest money laundering and financial crime risks are for their business based on data.

Doing risk assessment is a proactive step. In taking a cold, hard look at where money laundering threats could most likely appear, banks can do a better job of preventing crime in the first place. As a rule, being proactive costs less than having to investigate and manage a crime that has already occurred. Effective risk assessment economizes resources.

Customer onboarding is only the beginning of AML. Financial institutions must be vigilant throughout the customer lifecycle for transactions that are out of the ordinary, or may signal suspicious activity.

With more banking now digital, and customers increasingly expecting speedy transactions, monitoring has become more challenging. Money is moving around faster, and AML professionals sometimes struggle to keep up.

When something suspicious occurs within a financial institution, most governments require them to act on it.

A financial institution can officially signal suspicious behavior through a suspicious activity report (SAR).

Before filing a SAR, a bank needs to conduct an investigation to justify the report. Traditionally, investigations involve digging into multiple databases to pull out the relevant information. Since money laundering tends to fly under the radar by design, finding evidence to back up the suspicion that a crime has occurred can take a lot of time and dedication.

Once the bank has gathered sufficient evidence, they decide whether the initial suspicion holds up. If it doesn’t, the case is closed. But if it does, they submit a SAR to the financial intelligence unit (FIU) in the country where they are operating. After that, it’s up to the authorities to decide whether and how to criminally pursue the case.

If governments have passed more and more regulations to try to stem financial crime and financial institutions are spending record amounts to understand their customers, assess risk, monitor transactions, and investigate suspicious activity, why does money laundering remain such a problem?

There are a few reasons why effective anti-money laundering remains a challenge.

The way we bank, pay for things, and transfer money isn’t the same as it was even a decade ago. The use of cash has decreased dramatically.

It also goes without saying that the internet and smartphones have changed how we live and our expectations of the services we use. You can order a new pair of shoes online now and have them delivered to your doorstep tomorrow. In a couple of clicks, your favorite pizza can be handed to you in 30 minutes.

Everything moves fast, and people and businesses expect the same of their banking.

To keep up with client expectations, financial institutions have further developed digital banking and added new products to respond to the demand. Mobile banking and use of payment apps rose by 26% between 2019 and 2020, according to one report.

This evolution presents specific AML challenges.

- By going increasingly digital, banks have a tougher time verifying customer identity during onboarding.

- Faster transactions mean monitoring needs to speed up, too. Banks don’t have a lot of time to verify whether a transaction seems suspicious or not. Adding to this particular challenge is that there are increasing numbers of international transactions. More money moving across borders and jurisdictions means more challenges for those fighting financial crime.

- New digital products and services create more opportunities for criminals to take advantage of.

There is a long list of known money laundering schemes. They include smurfing, round tripping, trade-based money laundering, laundering through real estate, and more.

But criminals have always been creative when it comes to finding new vulnerabilities to exploit, taking advantage of new products, habits, and blind spots in detection systems. They’re also innovative when it comes to concealing wrongdoing. Such evolving criminal methodologies represent a major financial crime risk.

Cryptocurrency is another relatively new phenomenon that has been increasingly exploited for money laundering. The anonymity of crypto combined with few regulations makes it tempting territory for criminals.

New criminal techniques require a shift in thinking. Tackling each type of crime, each geography, each institution separately has become insufficient. It creates blind spots. Criminals are breaking down barriers, so the good guys need to do the same.

Financial institutions have all kinds of tools and technologies to fight money laundering.

Virtually all banks, insurance companies, etc. have an alerts system in place. These systems are built around simple rules that flag suspicious activities including transactions, account activity, etc.

The problem is rules-based AML alert systems result in a lot of false positives. Most financial institutions report seeing false positive rates of 95%.

It’s a big problem. First, false positives mean investigators are losing time that would be better spent investigating truly suspicious activity. Second, it can have a desensitizing or even demoralizing effect on anti-money laundering analysts.

The technology that many organizations use also doesn’t always meet the needs of today’s investigators. When investigating suspicious activity, organizations commonly use technology that relies on relational databases, with data displayed in tabs. It can take a long time to query relational databases, which are not designed to search for connections within the data. It requires the investigator to keep a mental map of the information they’re dealing with. It’s nearly impossible to see patterns beyond the individual case being investigated, which limits the investigator’s visibility over the broader context.

Furthermore, different departments may be using different tools to hunt down and stop criminal behavior. But often, criminals are working across sectors, as crimes like money laundering, fraud, and cybercrime converge. Siloed tools and data make it easier for them to slip through the cracks.

The ways that both banking and money laundering have evolved demand new ways of fighting back. Criminals are experts in finding new vulnerabilities and flying under the radar. This requires the people fighting money laundering to constantly adapt their way of working to keep up with—and stay ahead of—the bad guys.

Anti-money laundering has become like an arms race. Financial institutions are constantly looking for new tools to beat new criminal tactics.

Detecting new types of criminal activity is a challenge, and the task is made even harder by the data-related challenges financial institutions face. Many financial institutions simply aren’t seeing the big picture within their data.

Those challenges aren’t unsurmountable, though. To increase their volumes of data, organizations can borrow from more sources and use new tools to gain better insights.

Information sharing is one of the keys to making better use of data. Criminals don’t limit themselves to one type of crime, and sharing information can help catch money launderers even if they’re first caught committing fraud, for example.

Within organizations, this means sharing data across business units and geographies. The information gathered during KYC due diligence, for example, can be used by both AML and fraud detection teams.

The logistics of working and sharing data across units can be challenging since it can involve significant reorganization within financial institutions, but once the frameworks and procedures are established, it can really pay off.

Adopting new ways of fighting money laundering doesn’t necessarily mean getting rid of old systems. But layering new data, techniques, and technology on top of existing systems can help fill the gaps in an organization’s defenses and help them remain agile in the face of evolving threats. Putting in place a strategic tech stack and shoring up the different lines of defense helps organizations build a system that is more efficient overall.

Graph technology enables analysts and investigators to see not only data points, but the relationships between those points. It also helps unite data from different sources into one place, breaking data out of silos.

In AML investigations, seeing the relationships within your data is indispensable. Understanding relationships means understanding where and how money is moving, and who is connected to whom. Visualizing relationships within data can help detect suspicious patterns of activity and find new potential threats. This is especially true in a context where money laundering is frequently the work of complex, organized groups.

An investigation platform based on graph analytics, like Linkurious, facilitates and speeds up money laundering investigations. It makes data and relationships easy to explore. On top of that, visual information can be understood at a glance. It makes complex networks much easier to understand.

In a context of novel and increasingly complex money laundering and financial crime threats, graph technology can prove a powerful arm for financial institutions to defend themselves.