Procurement fraud has been a longstanding risk for both private businesses and government agencies. This type of fraud can cost organizations huge sums of money in inflated fees, subpar materials, and more.

A recent procurement fraud investigation of a manufacturing company with operations throughout Asia uncovered losses worth over $1 billion. Emerging markets are at particularly high risk for procurement fraud schemes, but businesses and governments around the world need to be vigilant.

This article covers the basics of procurement fraud: what it is, what procurement fraud schemes look like, and common red flags. We also look at how new analytics technology can help analysts detect and investigate a procurement fraud scheme.

Procurement fraud is the manipulation of a procurement process. In a typical scenario, a vendor is engaged for a contract above the market price in exchange for a kickback in the form of cash, material goods, or other benefits for the employee awarding the contract. Procurement fraud also includes the manipulation of the bidding process among vendors. And it can also include fraud that happens after the contract has been awarded, with a supplier delivering subpar materials for example.

Bad actors have many ways of carrying out procurement fraud. Some schemes involve collusion between an insider and a contractor; others involve illegal collusion among vendors. Some types of procurement fraud may occur simultaneously. Here are some common procurement fraud schemes.

In this scenario, an employee responsible for the procurement process favors one vendor over another or awards a contract above market price. They do this in exchange for kickback money, goods, or services.

Conflict of interest in a procurement process is when a vendor is selected based on a personal relationship: the procurement manager awards a contract to a friend or family member based on that relationship rather than on specific objective criteria. They may do this as a personal favor or in exchange for some kind of material reward.

Bid rigging involves collusion between vendors who manipulate the bids the business or government agency receives. Contractors may collude to offer identical prices, raise prices, remove competition, etc. In all of these cases, it’s the business or government agency that loses out.

This scheme occurs after a contract is won. The contractor swaps out the promised goods or products for other, cheaper ones and pockets the difference. Substitute goods may be sub-standard, faulty, not certified, falsely certified, not meet specifications, etc. This kind of scheme can end up being extra costly if the business or government agency in question needs to replace the faulty products or repair damage done by them. In extreme cases product substitution can also have a dire human cost (think of faulty medical devices or subpar construction materials).

Price fixing, closely related to bid rigging, is a collusive scheme in procurement fraud where vendors agree to manipulate bid prices, often to artificially inflate costs. Competing suppliers coordinate their bids, deciding in advance who will win the contract and at what price, thereby eliminating genuine competition.

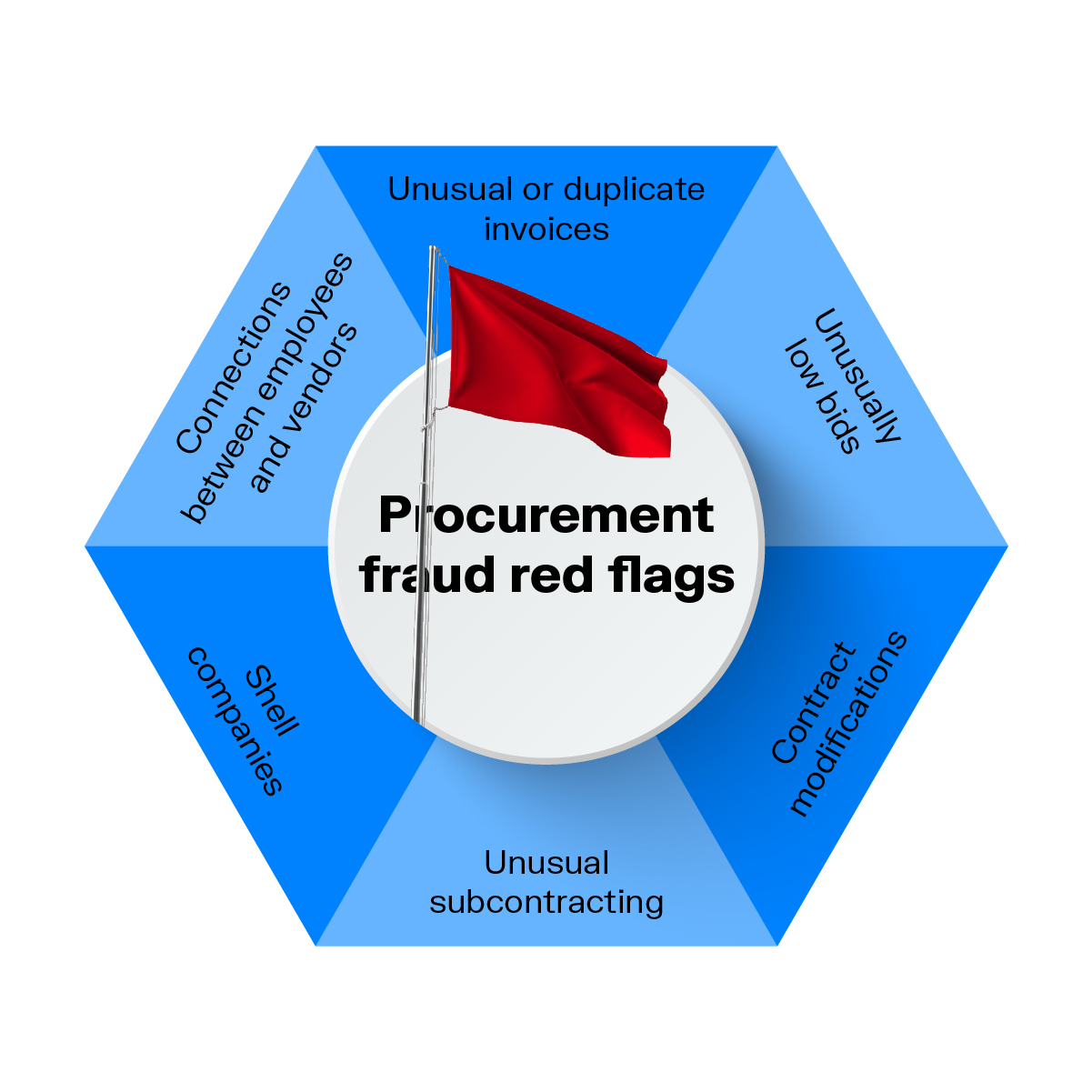

A first step to detecting and effectively investigating procurement fraud is knowing how to spot the red flags. Here are some common ones to look out for.

Corrupt suppliers may create extra invoices or issue invoices for inflated amounts. This may be done with the collusion of an employee.

One bid being obviously lower than the others could be a sign that the vendor may commit fraud (like product substitution) after the contract has been awarded. A late bid that is also low is also a red flag: it may mean the vendor has insider information to position themselves at an advantage.

An employee-vendor connection isn’t systematically suspicious. However, it’s problematic when an employee doesn’t disclose a personal, economic, or familial connection since this conflict of interest can prevent a fair bidding process.

Frequent changes to contracts, especially changes that increase costs, can indicate that fraud may be occurring.

If the prime contractors are subcontracting large portions of work to specific companies, it may be a sign of fraudulent activity.

Shell companies are a common cover for many types of fraud and financial crime. If a vendor has little to no online presence or lacks a physical address, it’s prudent to investigate further.

Procurement fraud can be hard to detect for several reasons, making it a difficult problem for auditors or investigators in government agencies and global companies to combat. Part or all of the scheme might be kept off the books and not immediately obvious. And bad actors typically take pains to conceal wrongdoing or red flags, such as personal relationships or shared interests.

Last but not least, siloed data in organizations increases the risk of bad actors flying under the radar and forces auditors and investigators to connect information manually before they can find evidence of procurement fraud after time consuming and tedious anti-fraud investigations.

The hidden ties between employees and vendors are often at the heart of a procurement fraud investigation, since most commonly a vendor is colluding with an employee. And if fraud is going on, the employee likely won’t have disclosed any connections.

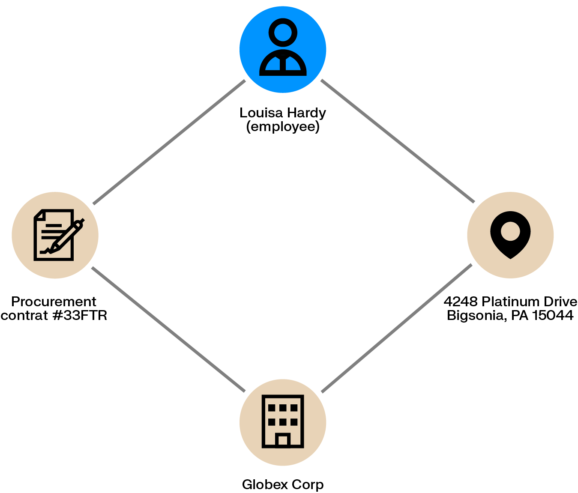

Because it’s natively built to analyze both data points and the relationships between them, graph analytics - or network analytics - is a powerful asset in procurement fraud investigations. Graph data is structured around nodes (individual data points) and edges or relationships (the connections between nodes.) Graph analytics quickly analyzes which entities are connected to each other and how.

Adding a graph visualization layer using a platform like Linkurious Enterprise enables you to see and analyze the connections you’re interested in in just a few clicks.

In the case of procurement fraud, connections between entities - employees, vendors, invoices, etc. - often represent the key indicators an investigator needs to uncover a fraud taking place. Graph quickly shows you these connections.

For example, with graph you can see if an employee shares an address with a contractor making a bid in a given procurement process. You can also analyze social media data to quickly understand if there are any social connections that raise a red flag. And if you have ownership data about your vendors, you can see if an employee has a financial stake in a supplier making a bid.

Network analytics is also an excellent tool to identify anomalies, including those that can be procurement fraud red flags. You can quickly spot if many invoices have been issued on the same date, for example, indicating potentially fraudulent activity on the part of a vendor. You can also see if there are anomalies in the invoice amounts, such as an abnormal number of small invoices when payments are typically large and infrequent, or larger payments than is typical with a given vendor.

By visualizing this information, analysts can quickly get to the bottom of an investigation.

A spotlight on graph technology directly in your inbox.